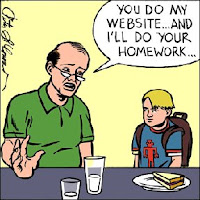

Changing attitudes to new technologies mean that the generation gap between teachers [“digital immigrants”] and those in their classes [“digital natives”] is perhaps greater than it ever has been. Young people today are wired differently, communicate differently, and study and learn differently to their predecessors. This has significant implications for education.

Whereas I protested to my parents [in vain!] that I could do my homework with either the radio or TV on, “digital natives” bring a whole new definition to multi-tasking – they think nothing of listening to iTunes, running MSN, Facebook, Hotmail, MySpace and YouTube simultaneously, whilst holding a number of conversations by text. It is no surprise that they have shorter attention spans, or that, because they have a more relaxed attitude to spelling and grammar when social networking, that this naturally spills over into their academic work. When faced with a new piece of technology – be it a mobile phone or a new computer program – they never read the instructions, they work out how to use it intuitively, and will ask a friend if they get stuck. They are used to being participants – even when watching TV – rather than being passive observers. They are used to being entertained – they are used to being involved. They inhabit a highly visual and creative world, where they share photographs and videos daily and are able to publish their creations to their friends or to the world in a matter of minutes. Young people inhabit a highly visual multi-media world of pictures and video clips, of scrolling information bars and instant updates. They piece information together from snippets of information. Like football fans watching Final Score, they select the information that is relevant to them, disregarding all other information.

One of the greatest challenges that faces teachers today is how to close the gap between the way in which young people are wired and the demands of the present British education system.

Clearly “Digital Natives” will still need to learn traditional skills and this will remain the case until such time that the examination system evolves to reflect better the way that both the worlds of work and of Higher Education operate. However, we need to recognise that we are, in effect, initiating young people into an alien culture that has different customs and speaks a foreign language. They are immigrants to the world of books, essays, and lectures. Their idea of research is informed by Google and Wikipedia, rather than the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Creativity for them is dominated by linking, cutting, pasting and “mashups” - and thus they have a fundamentally different concept of what is “original” work.

Nowhere is the difference between the generations seen more than in the exam hall. It is probably the only time in their life that young people are asked to sit and work unaided, in silence without the support of any technology. It is most likely that the examination system that will have to adapt; for the traditional examination hall is increasingly an alien environment, not only to our pupils, but also from the worlds of work and of Higher Education. [When does anyone sit and work unaided in silence without access to a computer anymore?]

Teaching has a long history of embracing new technologies and putting them to the service of education. If we are to engage fully with young people, we not only have to endeavour to initiate them into the customs of a more traditional view of education, but we also need to become fluent in their language too. YouTube, and the BBC iPlayer, for example, are extremely rich sources of quality educational content. Forward thinking teachers are producing podcasts to support the work which they are doing in the classroom that pupils can work through at their own pace on their iPod.

There is huge potential for young people will learn better if teachers harness the strong visual and creative aspects of their culture. Teachers who set the task, for example, of creating a video documentary or a multi-media clip are more likely to catch the imagination of young people than those who set a more traditional project. But there is more to this than motivation – the creative process itself brings insights can only learned through experience rather than through being taught. One significant consequence of this multi-media approach is that it accommodates the various learning types and enables each young person to learn from the medium that most suits them.

Whereas I protested to my parents [in vain!] that I could do my homework with either the radio or TV on, “digital natives” bring a whole new definition to multi-tasking – they think nothing of listening to iTunes, running MSN, Facebook, Hotmail, MySpace and YouTube simultaneously, whilst holding a number of conversations by text. It is no surprise that they have shorter attention spans, or that, because they have a more relaxed attitude to spelling and grammar when social networking, that this naturally spills over into their academic work. When faced with a new piece of technology – be it a mobile phone or a new computer program – they never read the instructions, they work out how to use it intuitively, and will ask a friend if they get stuck. They are used to being participants – even when watching TV – rather than being passive observers. They are used to being entertained – they are used to being involved. They inhabit a highly visual and creative world, where they share photographs and videos daily and are able to publish their creations to their friends or to the world in a matter of minutes. Young people inhabit a highly visual multi-media world of pictures and video clips, of scrolling information bars and instant updates. They piece information together from snippets of information. Like football fans watching Final Score, they select the information that is relevant to them, disregarding all other information.

One of the greatest challenges that faces teachers today is how to close the gap between the way in which young people are wired and the demands of the present British education system.

Clearly “Digital Natives” will still need to learn traditional skills and this will remain the case until such time that the examination system evolves to reflect better the way that both the worlds of work and of Higher Education operate. However, we need to recognise that we are, in effect, initiating young people into an alien culture that has different customs and speaks a foreign language. They are immigrants to the world of books, essays, and lectures. Their idea of research is informed by Google and Wikipedia, rather than the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Creativity for them is dominated by linking, cutting, pasting and “mashups” - and thus they have a fundamentally different concept of what is “original” work.

Nowhere is the difference between the generations seen more than in the exam hall. It is probably the only time in their life that young people are asked to sit and work unaided, in silence without the support of any technology. It is most likely that the examination system that will have to adapt; for the traditional examination hall is increasingly an alien environment, not only to our pupils, but also from the worlds of work and of Higher Education. [When does anyone sit and work unaided in silence without access to a computer anymore?]

Teaching has a long history of embracing new technologies and putting them to the service of education. If we are to engage fully with young people, we not only have to endeavour to initiate them into the customs of a more traditional view of education, but we also need to become fluent in their language too. YouTube, and the BBC iPlayer, for example, are extremely rich sources of quality educational content. Forward thinking teachers are producing podcasts to support the work which they are doing in the classroom that pupils can work through at their own pace on their iPod.

There is huge potential for young people will learn better if teachers harness the strong visual and creative aspects of their culture. Teachers who set the task, for example, of creating a video documentary or a multi-media clip are more likely to catch the imagination of young people than those who set a more traditional project. But there is more to this than motivation – the creative process itself brings insights can only learned through experience rather than through being taught. One significant consequence of this multi-media approach is that it accommodates the various learning types and enables each young person to learn from the medium that most suits them.

I think that OCR have grasped the issue you raise rather well with their new A level Media Studies specification. Given the heavy bias towards digital creativity in this subject, students are required now to maintain a blog, detailing their work, and to submit a digital evaluation of their coursework. This could be a DVD with extras (so, for example, a director's commentary, that explains how and why key decisions were made), a podcast, or the filming of a presentation that utilises multimedia presentation aids.

ReplyDeleteThere are the critics, naturally, who see this is as further evidence of 'dumbing' down. However, if you ask the students who undertake these projects what they think, they'll tell you that to plan, produce and distribute content, while working in a team, presents a challenging set of criteria.

Additionally, it's worth remembering that such students are studying Media in conjunction with other subjects.

As you note in your post, the world of work and higher education has more these days to do with the intelligent use of ICT, than it does with paper and pen.

I have noticed this year that the number of students coming to my department and asking to borrow a camcorder or Podcasting kit has increased. I believe this is because (a) this is the technology they know and they'd like to use it in an educational setting and (b) teachers themselves are coming to realise the numerous benefits inherent in offering digital technology as part of the learning mix.

We live, as the Old Testament saying says, in interesting times!

Looking into the future, assessment looks likely to be employer-led or even controlled. As a potential future employer, how would you assess candidates?

ReplyDeleteI watched a friend's son complete a challenging data response multiple choice type test to get into a law firm - it was very tough, impossible to complete in the time allotted - quick judgements had to be made (each problem had about 8 possible answers so luck could hardly play a part). If carried out under “exam” conditions, it would be a really useful test for identifying a potential employee.

Already we have the scenario where candidates are thrown together as a group and asked to prepare a multi-media presentation perhaps pitching for an advertising account, or potential journalists having to produce an on-line article showing their internet search abilities, or hopeful bankers “playing the stockmarket” ……..

So how would you prepare students for these types of assessments? Is there a future for national assessments such as the A Level? Schooling without formal assessment? Now, there’s an attractive thought! The mind boggles.

So many of the “challenges” mentioned here arise from young people thinking they know how to use the internet & IT/multi-media tools when what they actually know is how to use them technically. Researching on the internet is no different to researching the old fashioned way in books & journals – you still have to question the reliability of the source, identify the key information & be aware of how you can re-use material, both effectively & legally. If young people, & old, know this then the internet can be a very valuable research tool, if they don’t it can downright dangerous! Do we do enough to ensure young people know this? Do we really penalise plagiarism & reward novelty?

ReplyDeleteMulti-media offers a new range of exciting tools to capture attention & disseminate information but all too often people focus on the image of the work rather than the content. Adults are just as guilty of this – think of the overuse, & misuse, of powerpoint in some companies. These issues are particularly important as the use of IT & multi-media technologies move into every subject of the curriculum. Ultimately, we must ensure young people are taught to focus on what has to be communicated & why. If we do they will make much better choices about the how to do it. If they focus on the how they risk losing the “what” & the “why”.