The Context

Ch.1. A History of Misplaced Anxiety

A survey of the effect of technology on work over the past three centuries is characterised by two rival forces: a harmful substituting force which displaces human beings from performing particular tasks because the technology is faster or cheaper; and a helpful complementing force which raises demand for the work of humans to perform other tasks (e.g. the rollout of ATM machines did not replace bank tellers, but it meant that their role changed to provide customers with a better service p.26)The helpful complementing force to date has done this in 3 ways:

- the Productivity Effect: machines have made displaced workers more productive at other activities;

- the Bigger Pie Effect: technology has made economies and incomes around the world much bigger;

- the Changing Pie Effect: technology changed how consumers spend their incomes and how producers make goods and services available.

“Up until now, in the battle between the harmful substituting force and helpful complementing force, the latter has won out and there has always been large enough demand for the work that human beings do” (p.28)

Ch.2. The Age of Labour

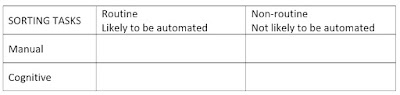

“a time when successive waves of technological progress have broadly benefited rather than harmed workers.” Autor-Levy-Murnane ALM Hypothesis: Machines could readily perform the ‘routine’ tasks in a job, but would struggle with the ‘non-routine’ ones (p.39) Technological progress is neither skill-biased or unskilled-biased it was task-biased (p.40).Ch.3. The Pragmatist Revolution and Ch,4. Underestimating Machines

Greek Poet Archilochus: ‘The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.’ p.64 – “we should be wary not of one omnipotent fox, but of an army of industrious hedgehogs” p.67)AI Purists (cognitive scientists) closely observe human beings acting intelligently and try to build machines like them. This approach and the quest for Artificial General Intelligence AGI, to date, has failed. (c.f. the omnipotent fox remains illusive)

AI Pragmatists (computer scientists) take a task that requires intelligence when performed by a human being and build a machine to perform it in a fundamentally different way – relying on advances in processing power and data storage. The quest for Artificial Narrow Intelligence ANI is proving quite fruitful (c.f. the army of industrious hedgehogs).

“The temptation is to say that because machines cannot reason like us, they will never exercise judgement; because they cannot think like us they will never exercise creativity; because they cannot feel like us, they will never be empathic. All that may be right. But it fails to recognise that machines might be able to carry out tasks that require empathy, judgement or creativity when done by a human being – but doing them in some entirely different fashion.” (p.72-73)

“We do not need to solve the mysteries of how the brain and mind operate to build machines that can outperform human beings.” (p.74)

The Threat

5. Task Encroachment

Technology is encroaching on all areas of work: Manual capabilities (agriculture, driverless cars, car manufacturing, construction industry, 3D printing); Cognitive capabilities (Law, Medicine, Education, Finance, Insurance, Botany, Journalism, Military – “Computational creativity”) Affective Capabilities (“affective computing”, “social robotics”)Task encroachment will be taken up at different paces. Because

- “some tasks are far harder to automate than others”;

- in some industries the cost of human labour is low and complexity of automation is high (e.g. cleaning, hairdressing, table-waiting);

- different cultures and jurisdictions will have different attitudes and regulations.

Ch.6. Frictional Technical Unemployment

“There is still work to be done by human beings; the problem is that not all workers are able to reach out and take it up” (p.99).Three reasons for this:

- A Skills Mismatch (work available for much more qualified or more skilful);

- An Identity Mismatch (work available but doesn’t fit will self-image – not a graduate job, or a man’s job – jobless lorry drivers may not want to do “pink collar” work such as child care);

- A Place Mismatch (the work available may be in a different part of the country/ world)

- there will be downward pressure on wages;

- there will be downward pressure on the quality of the work;

- there will be downward pressure on the status of the work available (rich-poor, master-servant divide).

Ch.7. Structural Technical Unemployment

In the future the Complementing Force is likely to be much weaker: 1) The Productivity Effect – “As task encroachment continues, human capabilities will be come irrelevant . . . for more and more tasks” (p.114); 2) The Bigger-Pie Effect – “a growing demand for good may mean not more demand for the work of human beings, but merely more demand for machines” (p.116); 3) The Changing Pie Effect – for consumers, “As task encroachment continues, it becomes more and more likely that changes in demand for goods will not turn out to be a boost in demand for the work of humans, but of machines” (p.119); and for producers, “As task encroachment continues, will it not become sensible to allocate more of the complex new tasks to machines instead?” (p.121).“It is a mistake to think that there is likely to be enough demand for them [human beings] to keep everyone in work” (p.124).For Susskind, at present there is an assumption that human beings are superior to machines; in future we may need to assume that we are inferior.

“Just as today, we talk about ‘horsepower’ harking back to a time when the pulling power of a draft horse was a measure that mattered, future generations may come to use the term ‘manpower’ as a similar kind of throwback, a relic of a time when human beings considered themselves so economically important that they crowned themselves as the unit of measurement” (p.130).

Ch. 8. Technology and Inequality

“The largest economic pies, belonging to the most prosperous nations, are being shared out less equally in the past” (p.137)The longstanding relationships between traditional (33.3%) and human capital (66.6%) is changing: Traditional Capital “is everything owned by the residents and governments of a given country at a given point of time, provided that it can be traded on some market” (p.133). Human Capital is “the entire bundle of skills and talents that people build up over their lives and put to use in their work” (p.134).

Susskind identifies three trends (p.146):

- “human capital is less evenly distributed”;

- “human capital is becoming less and less valuable relatively to traditional capital”;

- “traditional capital is distributed in an extraordinarily uneven fashion”.

“Today many people lack traditional capital, but still earn an income from the work that they do, a return on their human capital. Technological unemployment threatens to dry up this latter stream of income as well, leaving them with nothing at all” (p.149).

The Response

Ch.9. Education and its Limits

“’More education’ remains our best response at the moment to the threat of technological employment."We can do this in 3 ways:

- What we teach: “do not prepare people for tasks that we know that machines can already do better; or activities that we can reasonably predict will be done better by machines very soon” (p.158) N.B. “Many tasks that cannot yet be automated are found not in the best-paid roles, but in jobs like social workers, paramedics and schoolteachers.”

- How we teach: non traditional blended-learning and online learning methods need to become more commonplace.

- When we teach: we need to move to a world of life-long learning: “People will have to grow comfortable with moving in and out of education, repeatedly, throughout their lives. We will have to constantly re-educate ourselves” (p.160).

“Even the best existing education systems cannot provide the literacy, numeracy and problem-solving skills that are required to help the majority of workers compete with today’s machines” (p.165).

“Some people may cease to be of economic value: unable to put their human capital to productive use, and unable to re-educate themselves to gain other useful skills” (p.166).

“Education will also struggle to solve the problem of structural technological unemployment. If there is not enough demand for the work that people are training to do, a world-class education will be of little help” (p.166).

Ch. 10. The Big State

The role for the state in the C21 world without work is to deal with the looming disparities and inequalities in society. It will do this through taxation and redistribution of income and wealth. Taxation:- 1) taxing workers who have managed to escape the harmful effects of task encroachment;

- 2) taxing capital – taxing “the income that flows to owners of increasingly valuable traditional capital” (p.176);

- taxing big business – this needs to be tackled at a global level.

Redistribution: Susskind rejects the idea of Universal Basic Income (UBI) which has no strings attached. He has an excellent critique of the problems associated with membership criteria for UBI. He argues instead for a Conditional Basic Income (CBI) which requires recipients to contribute in some way (to be defined) to society. This is based on a view of ‘contributive justice’ whereby everyone feels that their fellow citizens are giving back to society. His vision is for a ‘Capital-sharing State’ and a ‘Labour-supporting State’.

Ch. 11. Big Tech

For Susskind, Big Tech companies are here to stay for two reasons:- Expensive Resources: it costs enormous amount to develop new technologies – huge amounts of data, world-leading software, and extraordinarily powerful hardware. Small firms cannot compete and talented ones just get bought out.

- Network effects – networks are more rewarding the bigger they get.

Ch,12. Meaning and Purpose

A world without work throws up philosophical questions about how human beings find meaning; and practical questions of how people will spend their leisure time: volunteering, unpaid work, community required activities (see Conditional Basic Income above).“A job is not simply a source of income but of meaning, purpose and direction in life as well” (p.215).In the C21 “Work is the opium of the People”. Work has meaning beyond the purely economic. “The problem is not simply how to live, but how to live well” (p.236).

Revisiting Education. Spartan King Agesilaus: ‘the purpose of education is to teach children the skills that they will use when they grow up.’ Perhaps schools should prepare young people for a world of leisure: character, virtue, life skills education.

“If free time does become a bigger part of our lives, then it is likely also to become a bigger part of the State’s role as well” (p.234)A world without work throws up three fundamental problems:

- the problem of inequality;

- the problem of political power;

- the problem of meaning.

This is an important book - essential reading for anyone who is interested in preparing young people for the future.

No comments:

Post a Comment